| About the Mission | About the Spacecraft and Impactor |

| About the Comet | About Comets in General | About the Encounter |

- What are the possible effects of a comet hitting the earth?

- How do astronomers know which asteroids or comets pass by us?

- Do we really know where comets and asteroids go once they leave our space?

- I am writing a report on comets and need more information.

- After water ice sublimates off the comet, what happens to it in the vacuum of space?

- I understand that the components of water, OH and H can be detected with ultraviolet spectra. Will the collision of the impactor spacecraft onto Tempel 1 cause any change in the fluorescent lines of OH?

- If the buried frozen gases and water-ice inside a comet nucleus are "electrically neutral" until ejected into the strong UV radiation coming from the sun, could there be electrical activity (lightning) occuring on comet nuclei?

- How did earlier cultures know when a comet returned?

- What is the difference between the nucleus of a comet and its core?

Q: What are the possible effects of a comet hitting the earth?

The effects of an asteroid or comet impacting the earth depends on the size and composition of the impactor. There is literally tons of material hitting the earth every day! Most of it is just dust and burns up in the atmosphere as shooting stars. On October 9, 1992, a fireball was seen streaking across the sky from Kentucky to New York. At least 14 people captured part of the fireball on videotape. Larger pieces may survive their fiery passage through the atmosphere to hit the ground. It is believed that a 10km wide rock hitting the earth 65 millions of years ago was responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Astronomers know which comets and asteroids pass by us by observing the path or orbit these objects take around the sun. Just like the planets and moons, asteroids and comets have orbits which can be mathematically calculated based on observations. These elliptical (egg-shaped) orbits are relatively unique. When a new asteroid or comet is discovered, astronomers have to observe it enough times to be able to determine the orbit. There are certain numbers they use to define the orbit and we call those numbers 'orbital elements.' We can use the orbital elements to predict the future positions of comets and asteroids within the solar system. All of the asteroids and comets that we currently know of have orbits that keep them in the solar system so they never really leave 'our space.'

I am writing a report on comets and need more information.

Although we would like to (in theory) make this website the most complete website on comets, we recognize our limitations. Plus there are already several very good sites on comets in general. A good place to start is on Small Solar-System Bodies. The Planetary Society maintains a list of comet missions. There also info about comet missions at the NSSDC. Another NASA site that has lots of information and pictures of comets is the Comet page at JPL. For some interesting activities try Amazing Space's Comets page. Finally, there is Gary Kronk's great website Cometography.com/.

Good question. Water vapor in the vacuum of space and when exposed to sunlight further breaks down in a process called photodissociation, into H atoms and OH molecules. The OH molecules fluoresce in the presence of sunlight and is detected with spectrometers sensitive to Ultraviolet light. In fact, we can measure the abundance of water in a comet's nucleus by measuring the intensity of the emission bands and applying some scaling factors.

Indeed, one of the products of water dissociation is OH, which produces emission bands in the near-ultraviolet portion of the spectrum by fluorescence. As seen from Earth, these bands would be expected to brighten following the projectile's impact with Tempel 1 similar to changes in any species' emission bands due to a change in the amount of gas in the coma. To first approximation, the intensity of the band is simply proportional to the number of molecules available to fluoresce. Whether the increase due to the impact is detectable depends on how much new water is dissociated compared with the on-going release of water from the rest of the comet's surface.

(Thanks to Dr. David Schleicher of Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, AZ)

PI Mike A'Hearn responds...

"Not likely - that phenomenon should not be significantly different from normal comets, for which there is no indication of lightning. The ionization happens so far from the nucleus that the voltage gradient is tiny. The separation between electrons and positive ions in the outer coma is relatively small, so that the overall coma is electrically neutral. Recombination doesn't happen because the density is so low, which also inhibits the electrical conductivity even if the material were totally ionized."

Prof. Chris Russell of UCLA's Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics and PI for the DAWN mission responds... "Lightning on Earth arises due to the charging up of water droplets and the separation of droplets of different size (and therefore charge) by the convection of droplets upward in clouds. Thus gravity in maintaining an atmospheric pressure gradient is also a needed factor in terrestrial lightning generation. Since on comets gravity is weak, and the pressure and temperature of the gas is not right for water droplet formation we do not expect lightning to occur. However, nature often surprises us. So one should be vigilant."

How did earlier cultures know when a comet returned?

Actually, early cultures where not even aware of comets as being icy bodies in the Solar System. So every comet they saw was a 'new' demon in their belief system. It wasn't until the late 1600's that astronomers thought that some comets that had been observed through the centuries might be the same comets seen over and over. In fact, the "first" comet that is defined as periodic, meaning that it is seen on a regular basis, is comet Halley. It is named after Edmund Halley who noticed that every 76 years there was a comet visible. He was able to predict when that one comet would return. Unfortunately, he died before he could see his prediction come true, but the comet was still named after him. How was he able to predict the return of this comet? Well, every comet has a very distinctive orbit or elliptical path around the sun. That orbit can be defined with a set of numbers that we refer to as "orbital elements." Since the path of the comets (and the planets) are in three dimensional space, we need at least 3 numbers to orient that path, a few others to define the size and shape, and a few to define the position in the orbit. Using these orbital elements, we can then calculate a comet's past and future positions to predict when it will next be observable. If a comet is found by chance, one has to observe it long enough to trace its path on the sky, fit it to an ellipse to determine the orbital elements, then compare those values to a table of known comet orbital elements to identify it.

What is the difference between the nucleus of a comet and its core?

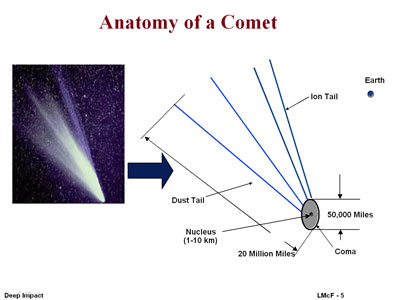

The nucleus of the comet is its solid part that is embedded in a cloud of gas and dust called the coma. The term arises from our perception of the comet as an observational phenomenon, of a fuzzy ball of light with a tail. The nucleus would then be the center of the phenomenon. Until 1986 when the Giotto spacecraft flew past Halley's comet, we had never seen the nucleus of any comet.

Now that we can get close to a comet and study it in more detail, we start to talk about the parts of a nucleus going into its interior. We ask if there is a 'crust' of the nucleus which is the top layer that has been processed by devolatilization (the removal of icy materials). Is there a 'mantle', which is a layer that is denser than the crust. Since the layering implies some processes involving heat and alteration of material, we then can hypothesize a cometary 'core', which is the very center of the solid part of the nucleus. We don't know the nature of the crust, mantle or core of the comet or even if they exist. In the Deep Impact mission we plan on finding out if layering exists and if it does, to study the crust and mantle of the comet.

|

| Hi-Res JPEG (134 KB) |